Royal saltworks of

Arc-et-Senans is a beautiful historical factory used to extract salt during 18th

and 19th centuries, which is now listed in UNESCO’s World Heritage

Sites. It is located in eastern France, in the city of Chaux and right next to

the forest Chaux. The architect was Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, a famous royal

architect during the reign of Louis the 15th and the Louis the 16th.

The construction began in 1775 with the approval of the king (Louis the 15th)

and finished in 1779, ten years before the French revolution has started. When

it was finished, Louis the 16th was ruling the country, so his name

was carved on the entrance. Although the first plan in a square form was not

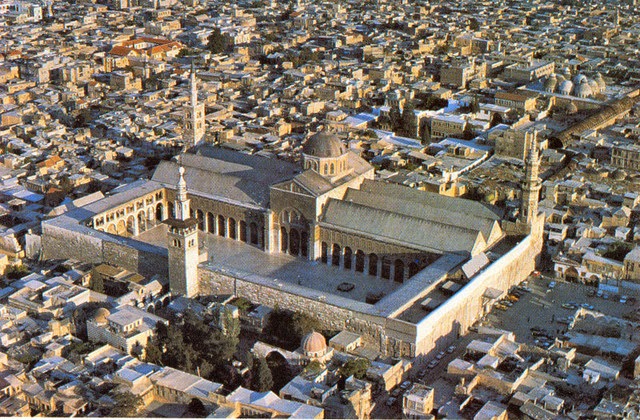

accepted, Ledoux was successful with his second plan, which was in a semi-circular

pattern. The realized plan has eleven stone buildings around the semi circle

consist of a monumental entrance (including a wash house, bakery, prison and a

guard post), administration building, two workshops on the left and right sides

of the administration building, four buildings for the labors, two pavillions

for taxes and a stable. Wood was another element used in the construction. It was

also a significant element in salt making and, unfortunately, it started to

diminish as time passed. Ledoux decided that carrying wood would cost higher

than transporting water. So, he also built a 20 km canal from Saline to the

forests. As a whole, Ledoux’s saltworks constructed on a fifteen km square area

is a unique masterpiece in terms of ornament, form, function, material and

technology used, and style.

The site welcomes you with a

magnificent entrance. It has eight Doric columns which represent the birth of

architecture since Ancient Greek. Behind the columns, there are sculpted stones

and an artificial grotto. If we consider the entrance as a theater stage, the

columns would be the curtains that cover the surprising cave at the back. If we

analyze the alignment of the entrance, administration building and the stable,

we can also say that it represents an evolution, which starts from a cave

(grotto) and ends with a temple (administration building). Furthermore, Ledoux

wanted to build something more original with the columns and established a new form

for the administration and management building at the center where he used the

columns for the second time. This new order was a combination of cubic and

cylindrical stones that were put one after another. Other essential motifs are

seen in the shape of vase and pouring water situated on the outer walls of the

work stations in order to glorify the decoration.

( Artificial Grotto )

(the motifs on the walls)

(the original columns in front of the administration building)

( Doric columns in the enterance)

Simple geometrical

shapes such as circles and quadrangles were used in the form of the site.

Ledoux was a perfectionist. He prevented everything that contradicts with the

simplicity. For instance, the buildings do not have chimneys. (The windows

facing the walls are used to get rid of the smoke and to air the buildings. The

windows facing inside the site are only used for decoration) Woods and gardens are

situated at the back of the semi circle right next to the diameter since he

wanted to conserve the huge open space in the middle. There is a harmony

between the buildings and the green area. The buildings are ordered in terms of

superiority and purpose. The buildings that are related to production are

aligned in the diameter, whereas the lodgings are located on the arc. Additionally,

rectangle-shaped stones are used around the windows, doors and the corners. The

variety in tecture, color of the stones and bricks also signify the hierarchy.

For instance, the administration building stands out more since its collosal

volume and original columns placed in the front while it is ornamented with

beautiful stones.

Furthermore, the

saltworks has been used for many different purposes throughout the history. The

salt making activities continued in the royal saltworks until 1895. At the

beginning of the 20th century, the site housed Spanish refugees. In

1940, German troops used it as a residence. In the following years, the site

was used as a concentration camp for gypsies. Luckily, in 21st

century, Royal Saltworks provided much better facilities compared to the last

century. Now, the site is open to public. There is a museum dedicated to Ledoux

which hosts events and exhibitions going on throughout the year.

Interestingly, the power of

authority is seen all around the site. The shape of the site looks like an eye.

And the hole at the top of the administration building gives the feeling that

people are watched all the time inevitably. The huge green section and the

alignment of the buildings in a semi-circular shape increase security.

Moreover, the semi circle site is covered with a wall to isolate the area. It

protects the factory from both internally and externally. All the workers were

controlled before they quit in order to protect the valuable salt. On the other

hand, it was also a helpful tool to keep the facory away from the external

threats such as refugees hidden in the forest or smugglers. Ironically,

Ledoux’s utopic site reminds me of “1984”, George Orwell’s dystopia where

citizens were watched all the time and got orders from the government. They

were never able to see the ruler but always felt his existence. The hole at the

top is a powerful symbol for authority.

Additionally, the novel technique Ledoux used

in the columns of the administration building is a groundbreaking development considering

the classical usage of columns since the Ancient Greek period. The site is also

one of the first examples of industrial architecture. Ledoux is a philosopher

architect who uses geometry in a very meaningful way. He creates a wonderful

site both functionally and aesthetically.

Citations

"Claude Nicolas Ledoux, La Saline De Chaux,XVIII° ,

(analyse Simplifiée )." - Art Air(e) " Arts Plastiques" N.p.,

n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

La Saline D'Arc Et Senans [part 1]. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3UxmwvemB4>.

La Saline D'Arc Et Senans [part 2]. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_5qq149RcbI>.

"Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans." Wikipedia.

Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

"Www.salineroyale.com." Www.salineroyale.com.

N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

Photographs used

in the paper

Birdseye view of the site. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. 11

Feb. 2014.

Digital image. Http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/thumbs/site_0203_0019-500-342-20100504121949.jpg.

N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

<http://farm6.staticflickr.com/5305/5623811603_5d6945555b.jpg>.

Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Feb. 2014. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiJ_GkkoFgeqF8eQOVDEWenMmZ8sSHzwvwWJ35cABpgBCqnCSbDadBcXTPlaSUYSdoO2uJ-Sk1HmOogNjvWC-ud_6X9_vNzaYT_EL45FC0OSWVDPULiy4c0RwwdYwmqswlCgD1uWUz21AE5/s1600/IMG_5355.jpg

The Motif on the Walls. Digital image. N.p., n.d.

Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

<http://media-cache-ec0.pinimg.com/236x/8e/26/73/8e2673e56cb881875a5006368bedf403.jpg>.