What is Islamic Art? What

is Islamic Architecture? Did the early-Islamic structures have a novel form or

were they derived from previous cultures? Were early-Islamic mosques built in

order to gather the Muslim society or were they built with an aesthetic sense?

These are the questions Oleg Grabar answers in the “Islamic Religious Art: The

Mosque” section of his famous book called “The Formation of Islamic Art”. In

order to understand the common features used in the latter mosques, he mainly

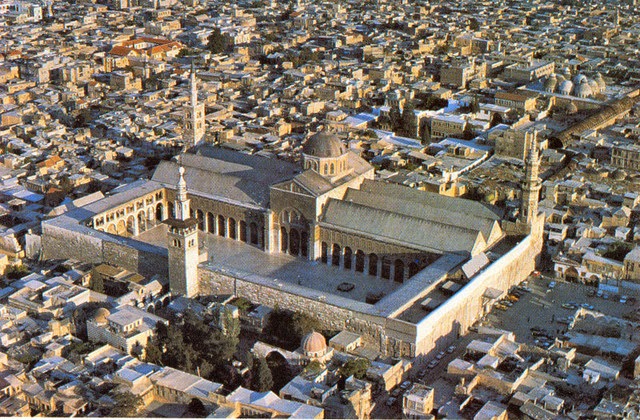

focuses on the structures of Umayyad mosques such as the Great Mosque of

Cordoba in Spain (fig. 1.a and 1.b) and the Great Mosque of Damascus in Syria

(fig. 2), also Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem (fig. 3) and the Prophet’s house in

Madinah.

He

first analyzes the word ‘masjid’ using its appearances in the Quran to

understand the origin of the mosques and reaches the conclusion that it only

means “sanctuary, a place to worship” which is far too general to refer only to

the Islamic mosques. The need of an architectural structure, mosque, emerged

from a statement in Quran, which requires a gathering in Fridays to perform

prayers. Allowing the Muslims to pray anywhere and on their own for the rest of

the time, Quran emphasizes the Friday noons with these words in 62nd

surat and 9th verse, “O you have believed, when (the adhan) is

called for prayer on the day of Jumu’ah (Friday), then proceed to the

remembrance of Allah and leave trade. That is better for you, if you only

knew.” The only place for this gathering was the Prophet’s house, which really was

his home at first and then transformed into a holy mosque. Besides the house,

other small formations were created around Medina and they were called

“musallah”. Unfortunately, none of these early structures had survived.

Since there were no

existing mosques earlier than the 8th century, he examines the early

Umayyad mosques: The Great Mosque of Damascus and Cordoba assuming that

especially the features they both share may be considered as the

characteristics of the spaces that were used in mosques in earlier centuries.

The common characteristics of the nonexistent early are:

·

Large rectangular shaped plan

·

Large courtyards

·

Surrounded by porticoes on three sides

·

Large halls with naves on the fourth side

He tries to explain the reason why the plan of a

mosque had changed between the Early Islamic period and the future centuries

from a simple rectangular form to a much more complex structure. It is for sure

that the masjids were embracing the whole Muslim society in the city since the

beginning of the Early Islamic period. The growing population led to a

development in the plan of the mosques. It was once a single rectangular unit

consisted of an open and a closed area (fig. 4), then developed into two parts:

a courtyard and a closed area with a façade. This implies that mosques were

built to meet social needs rather than architectural or aesthetic conceptions.

While examining the early

structures, Grabar highlights the differences of the hypostyle hall for a

mosque that is distinguished from the hall in a church. In a church, the hall

is wider than the side aisles and the naves are parallel to each other. On the

other hand, the size of the hall does not vary in a mosque and the direction of

the naves is perpendicular (fig. 5). He suggests that the early hypostyle hall

was inspired by the house of the Prophet instead of the halls in a church. He

also points out that the columns are reused in the construction of the mosques

such as the mosque of Damascus from Christian churches. So, we understand that

it is also very natural to use the existing art forms when trying to formulate

an artistic voice for a new formation. According to Grabar there are five

distinguished features of Islamic architecture:

1. Minaret

2. Mihrab

3. Maqsurah

4. Domed unit in the court

5. Axial nave ends up in

kiblah

These features are explained in the article in thoroughly.

The one that I found most interesting was the “minaret”. It is the part where

the Muslims are called for prayer. He mentions the two different types of

minaret: In the first one, it is attached to the mosque and has a rectangular

shape (fig. 6). The other one is located apart from the mosque and has a

cylindrical shape. This kind of a minaret exists in the Great Mosque of Samarra

(fig. 7). The most interesting part is where he states that the calling for

prayer has always been a need since the rise of Islam whereas the usage of the

first minaret is seen in the Great Mosque of Damascus (fig. 8). The towers of

Damascus from early Christians were convenient for this task. In conclusion

Grabar states that, “It is thus fairly simple to conclude that a certain

function appeared fairly early in Islamic mosques and that the forms used for

it were taken from older architectural vocabularies and therefore varied from

area to area.” And he believes that a structure keeps it originality when it is

reused for another function. So, the society puts a totally new meaning to an

old tower.

After explaining the

minaret feature of the mosque, I would like continue with the developments in

the mosque structure. The single form of the mosque varied only with the growth

of different branches and sects of Islam, which had varied needs that could

have been satisfied with differing architectural forms. These may have involved

various religious symbolisms and at times mystical interpretations:

1- Typical mosque buildings

2- Islamic function acquired

monumental form such as madrasa, mausoleum, tomb or ribat

Grabar

tries to determine which structural elements of the early mosques are

specifically Islamic and are not remainings of a pre-existing tradition. While

doing that, he describes the various decorative ornamentation techniques found

in a wide variety of examples of mosques from a huge geographical area. In

conclusion, he touches upon a significant question in Islamic art. Was the

decoration just for ornamentation or did it have an essential meaning? For the

decoration of the mosques, he suggests two variations:

1-

Concentrating the decorative elements around the sections of

the mosque to focus attention to these parts. (nave or mihrab (fig. 9))

2-

Distributing the decorative elements to emphasize the overall

unity of the mosque.

He also speaks of paradisiacal symbolism. Whatever

these symbolic meanings may have been in early mosques, they were later lost

since they started to become insignificant to the beholders. The reason for the

interpretation is obvious when we observe the Mosque of Cordoba (fig. 10). Moreover,

the only exception is the Arabic writings on buildings, which are more than

just decorations for Islam. Since it does not exist in the early mosques, this

is considered as a development of later periods.

The

text had enlightened me about the formation of a mosque and the early Islamic

structures. Grabar uses several examples and also points out the exceptions in

each case to support his arguments. What I have learned from him is that,

although the most of the early Islamic architecture did not have any elements

that were new inventions but were adapted from pre-existing forms, it is

important to understand that it is impossible to confuse a Muslim mosque with a

pre-Islamic structure.

Figure 1.a

The Great Mosque

of Cordoba

Figure 1.b

Interior of the

Great Mosque of Cordoba

Figure 2

The Great Mosque

of Damascus

Figure 3

Al-Aqsa Mosque

Figure 4

The diagram of the

Prophet’s house in Medina

Figure 5

The plan of the

Great Mosque of Damascus to point out the perpendicular naves used in the

mosques

Figure 6

The Great Mosque of Kariouan to show an example for

the rectangular minaret type attached to the mosque

Figure 7

Minaret of the

Great Mosque of Samarra to show an example for the cylindrical separate minaret

type

Figure 8

The minaret of the

Great Mosque of Damascus

Figure 9

The mihrab of the

Great Mosque of Cordoba

Figure 10

WORKS CITED

Grabar,

Oleg. "Islamic Religious Art: The Mosque." The Formation of

Islamic Art. New Haven: Yale UP,

1973. N. pag. Print.

Grabar, Oleg. The Formation of Islamic Art. New Haven: Yale

UP, 1973. 113. Print.

"Surat

Al-Jumu`ah (The Congregation, Friday) - سورة الجمعة." Quran.com.

N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Mar. 2014.

surat no: 62 verse: 9

Bird's eye view of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Digital image. N.p.,

n.d. Web. (fig. 1.a)

The Great Mosque of Cordoba. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. (fig. 1.b)

The Great Mosque of Damascus. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. (fig, 2)

Al-Aqsa Mosque. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. (fig. 3)

The Diagram of the Prophet’s House in Medina.

Digital image.Http://knoji.com/images/user/Slide3(20).jpg. N.p., n.d.

Web. (fig. 4)

The plan of the Great Mosque of Damascus. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web.

(fig. 5)

Minaret of the Great Mosque of Kariouan. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web.

(fig. 6)

Minaret of the Great Mosque of Samarra. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web.

(fig. 7)

The minaret of the Great Mosque of Damascus. Digital image. N.p., n.d.

Web. (fig. 8)

The mihrab of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Digital image. N.p., n.d.

Web. (fig. 9)

The courtyard of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Digital image. N.p., n.d.

Web. (fig. 10)

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder